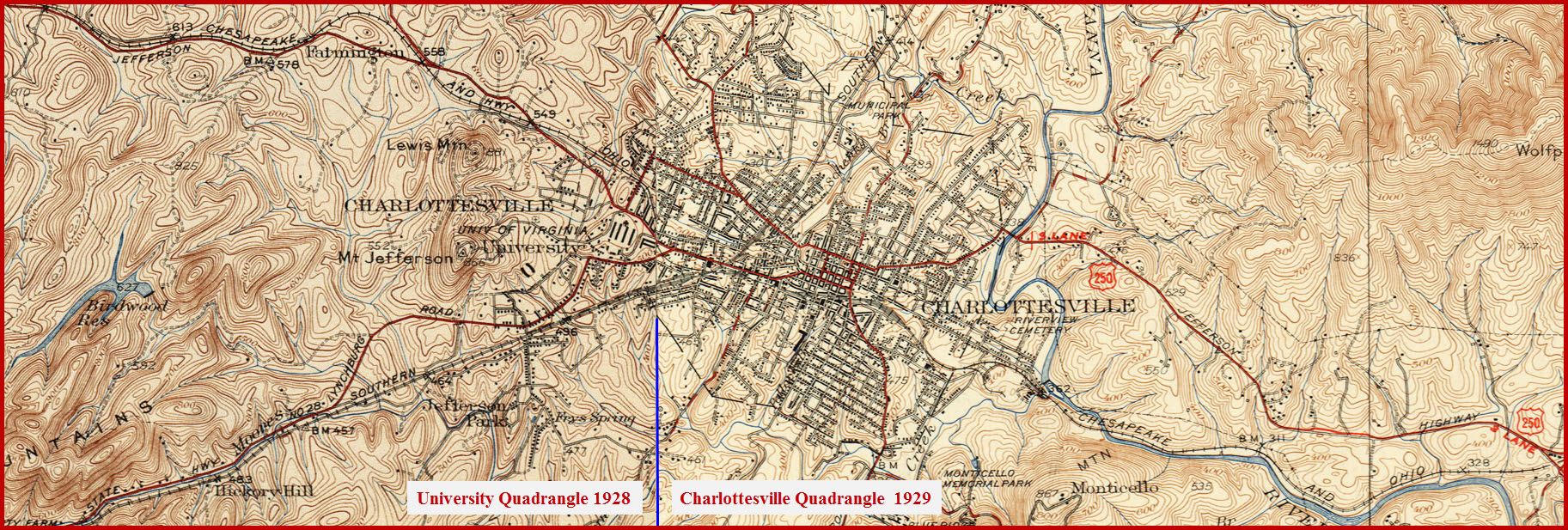

Prior to 1850, traveling from Richmond to Charlottesville took all day and involved hopping off the train in Taylorsville to hitch a ride the rest of the way on a stagecoach. The first train pulled into Charlottesville on June 27, 1850, arriving at the newly built station at the east end of town. After 1850, you could take the train the whole way and make it to C’ville in time for lunch. The population of Charlottesville subsequently jumped from 1,890 in 1850 to 2,600 in 1853, and the University of Virginia, which in 1855 got its own train station, saw its enrollment increase by almost 300 students over the next few years.

In 1864, Union General Philip H. Sheridan was sent into Virginia with orders to “[do] all the damage to railroads and crops that you can.…we want the Shenandoah Valley to remain a barren waste.” Sheridan’s campaign through the valley was called “The Burning,” and although Charlottesville was basically left alone, Sheridan did drop in and burn down the train station.

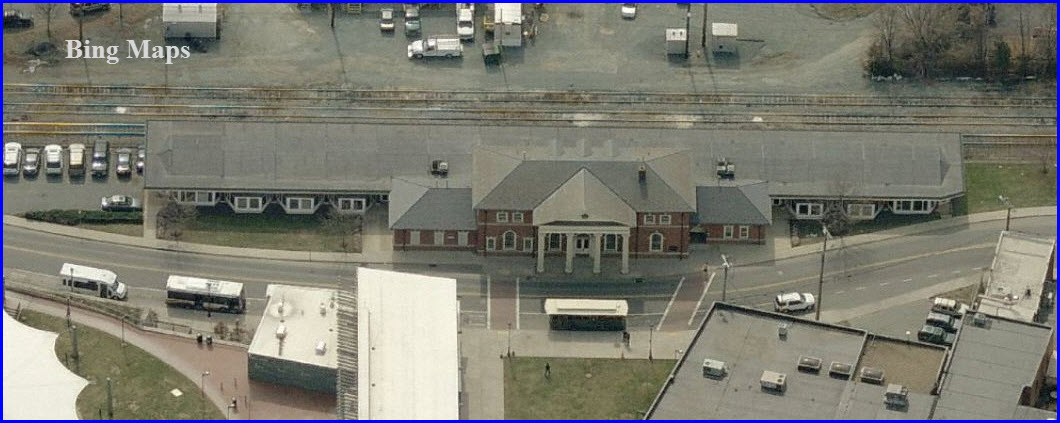

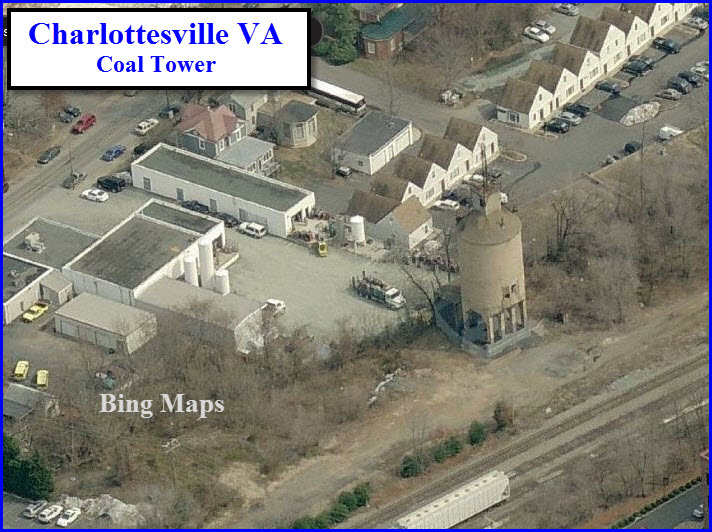

When the war ended, the station was rebuilt, and by 1870, Charlottesville was the busiest stop on what was now called The Chesapeake & Ohio line. In 1905, the wooden station was replaced by a grand, colonial mansion, brick with white columns, signifying the importance of the railroad in a newly powerful America. Thirteen trains a day were running through town by the 1920s. The Charlottesville freight yard was crowded, busy and big, covering the entire area between East Market Street, Carlton Road, and the end of the Downtown Mall. There was a semi-circular building called a roundhouse where the trains were serviced, a sand tower, a water tank, several wooden tool houses, an inspection pit, and a 115′ wooden turntable where engines could be turned around and sent back down one of the many tracks reaching out like fingers.

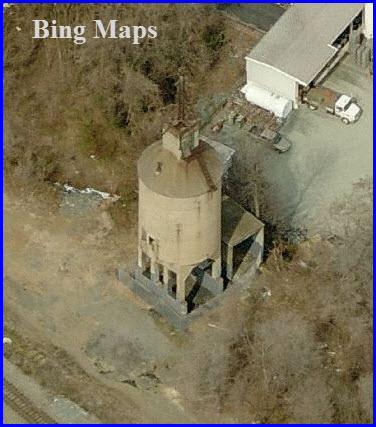

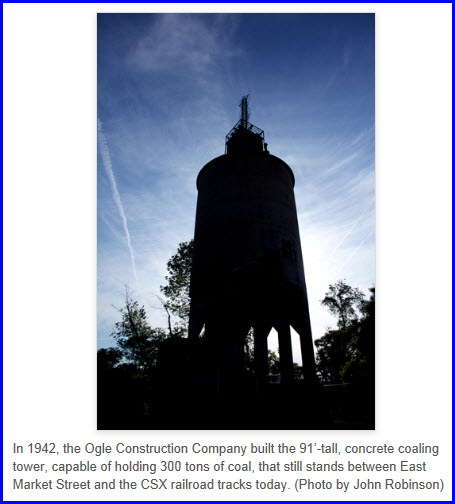

The first steam locomotives ran on wood, a few on oil, but after the Civil War, coal became the railroad’s dominant energy source. So you needed coal and you needed a way to get it into the trains. At first, stations relied on a pile of coal and men with shovels, but by the end of the 19th century, most train depots had elaborate towers to house and dispense coal to the waiting trains. Early towers were made of wood, later towers steel or concrete. By the 1940s, some stations had towers that stood hundreds of feet high and spanned multiple tracks. The Charlottesville station had a wooden coaling tower originally, until in 1942 the Ogle Construction Company built a 91′-tall, concrete bullet capable of holding 300 tons of coal.

from

from

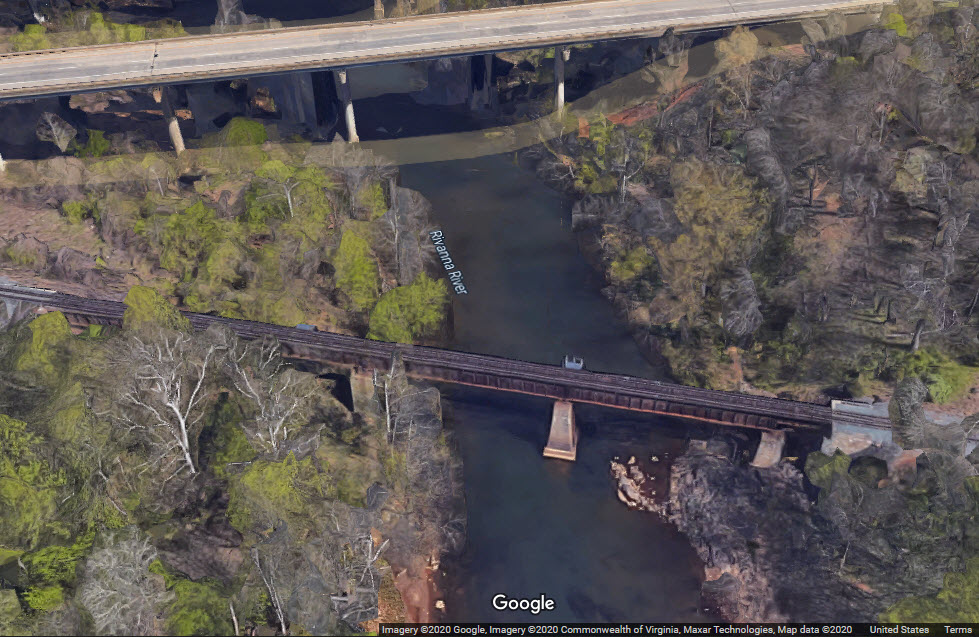

from County Road 859

from County Road 859

from Bridgehunter

from Bridgehunter

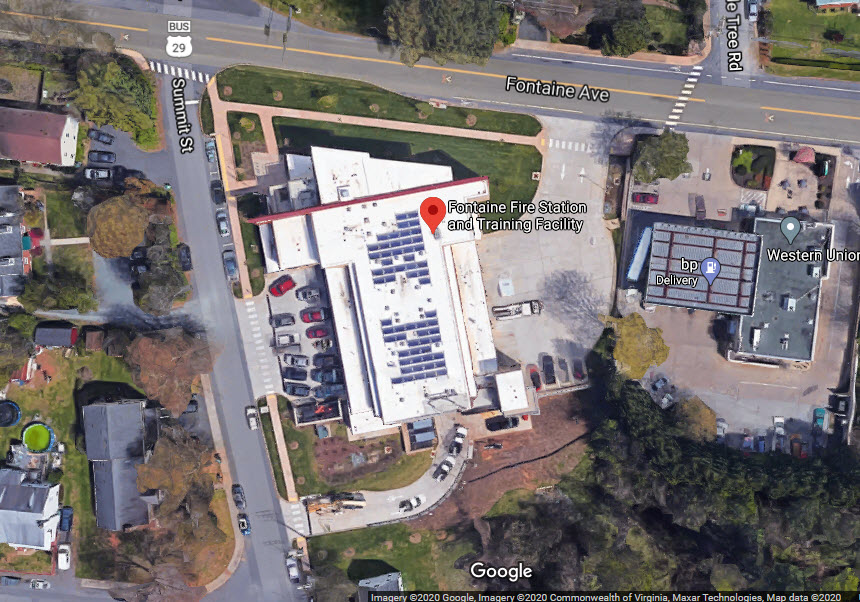

These pictures are from their website

These pictures are from their website

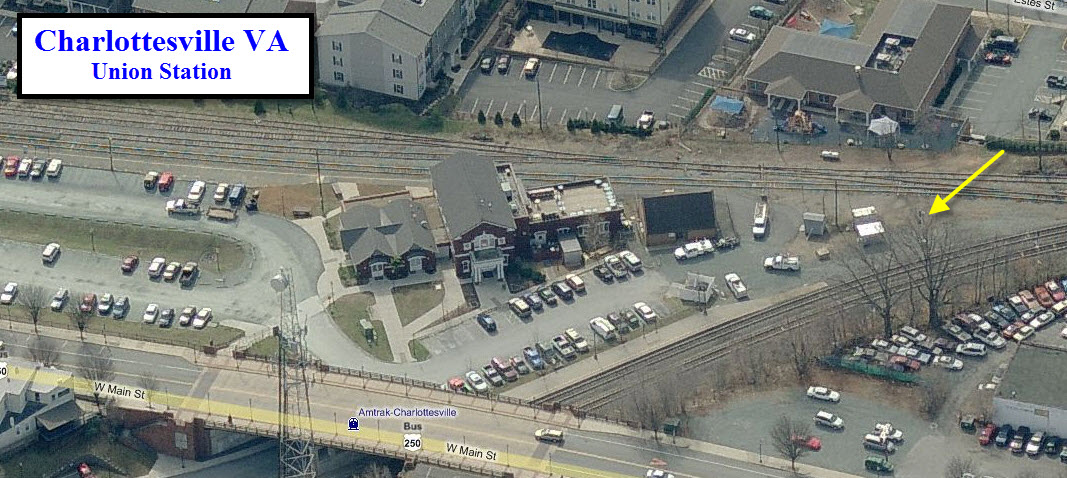

parked outside the station...

parked outside the station...